Your language teaching mission, should you choose to accept it, is to use the Drama Grammar method to structure improv lessons in your classroom that are grammatically focused.

This is Part II in a two-part series about the Drama Grammar method created by Susanne Evens. In the first post I explored the method, as outlined by Evens in her 2004 and 2011 articles. In this post I will be explaining how I would adapt Drama Grammar for my particular context (middle and high school students) and teaching style.

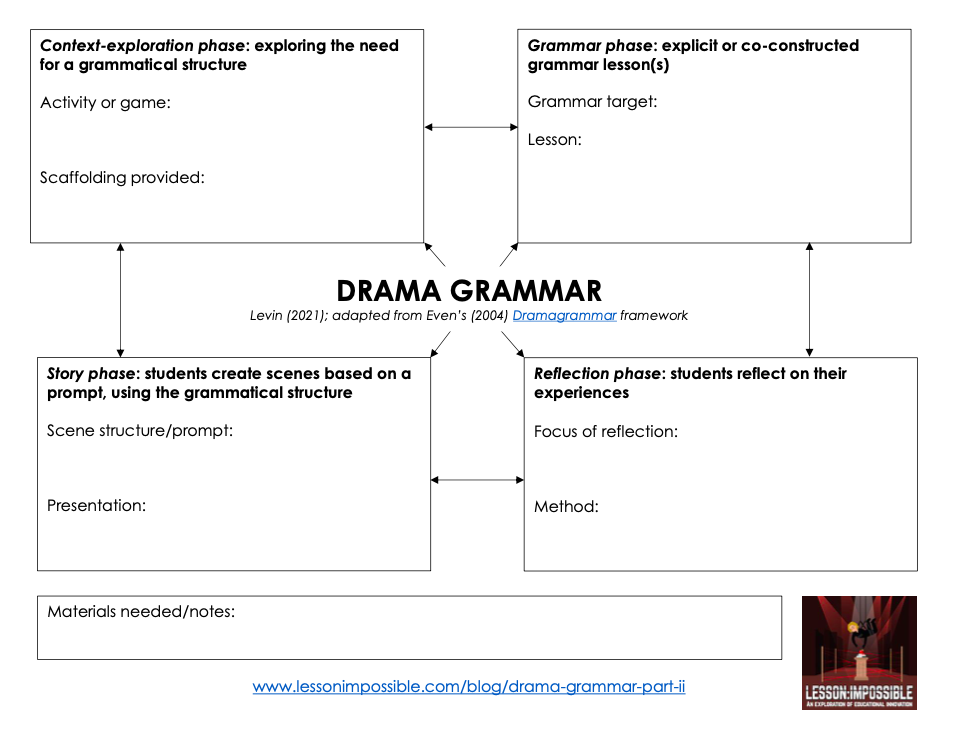

SCROLL DOWN TO DOWNLOAD THE DRAMA GRAMMAR TEMPLATE

The framework proposed by Even is fantastic, and as I outlined in my previous post, has a lot that I like about it! However, for use in my own classroom, there are a few adaptations that I wanted to make, such as making it a non-linear and reducing it to four phases. What I wanted to address by revising the framework was:

It seems from her articles that Even has an almost exclusive focus on Drama Grammar in her second language classroom. While I really like the model, I wanted something more flexible and easier to integrate into other lesson plans.

Even taught second-year German to students at the University of Leicester for a full academic year; I teach younger students (ages 13-18) and do not have a full year with them. I wanted to have a framework that would work for shorter attention spans and shorter class times. Therefore, the awareness-raising and context-finding phases can be combined into one phase of ‘context-exploration’.

Moreover, four phases fits nicely with the Systemic Functional Linguistics model of the teaching-learning cycle (Gebhard, 2019; Gibbons, 2015) which begins with “building the field or context” as its first step

While I understand that the context-finding phase is trying to create an authentic need for the language structure, I think that it is difficult to mimic real-world contexts in a classroom using a game or activity. Rather than try to force this, I would put the emphasis on finding authenticity in the scenes being created by students. I think just creating a need for a grammatical structure in order to play a game can be enough.

Even used a lot of process drama techniques and activities (such as teacher-in-role, co-constructing, hot-seating, assuming the mantle of the expert, etc.). While I think there is value to process drama, I tend to favor the more classic improvisational games, which can tend to be more goofy and less focused on creating authentic contexts (see above).

The presentation phase is, by its name, focused on presentation of scenes. I would like this to be optional, and focus more on the dramatic play phase, as I want to be more process orientated than production orientated (see here for further discussions on how drama can be conceptualized in the classroom). Therefore, the two phases are combined into a ‘story phase’ to put the emphasis on the narrative being co-constructed by students.

I don’t want to be confined to a liner model. Instead, the phases could easily flow into each other or be moved around. For example, students could weave between the context-exploration phase and the grammar phase, or alternatively the grammar phase and the story phase, as the teacher adds in more information. Alternatively, students could be in the story phase, be asked to reflect, and then return to the story phase to make adjustments based on their reflections before presenting.

Therefore, for use in my own classroom, I would break the Drama Grammar method into these four phases:

Context-exploration phase: the need for a structure is introduced through small games or scenarios. Students may be given sentence stems or models, though grammatical instruction is not given at this point.

Grammar phase: explicit or co-constructed grammar lesson(s) occurs.

Story phase: students create scenes based on a prompt (visual, textual, or vocabulary, etc.) and focus on incorporating the newly learned grammatical structure. Presentation can be to the whole group, another smaller group, just the teacher, or to no audience at all. (If you’re looking for some different prompts to start your scenes, check out this post!)

Reflection Phase: students reflect on their grammar use, but also their ability to tell a story, cooperate with peers, and engage with their own learning.

I was explaining these ideas to a friend recently and joked that it’s now the (L)even model of Drama Grammar: it’s all Susanne Even’s ideas but I, Aviva Levin, have come along and changed it up a bit! Joking aside, I wanted to share with you the planning sheet I created to help facilitate my own lesson construction:

DOWNLOAD RESOURCE (.DOC): Drama Grammar Planning Template.docx

DOWNLOAD RESOURCE (.PDF): Drama Grammar Planning Template.pdf

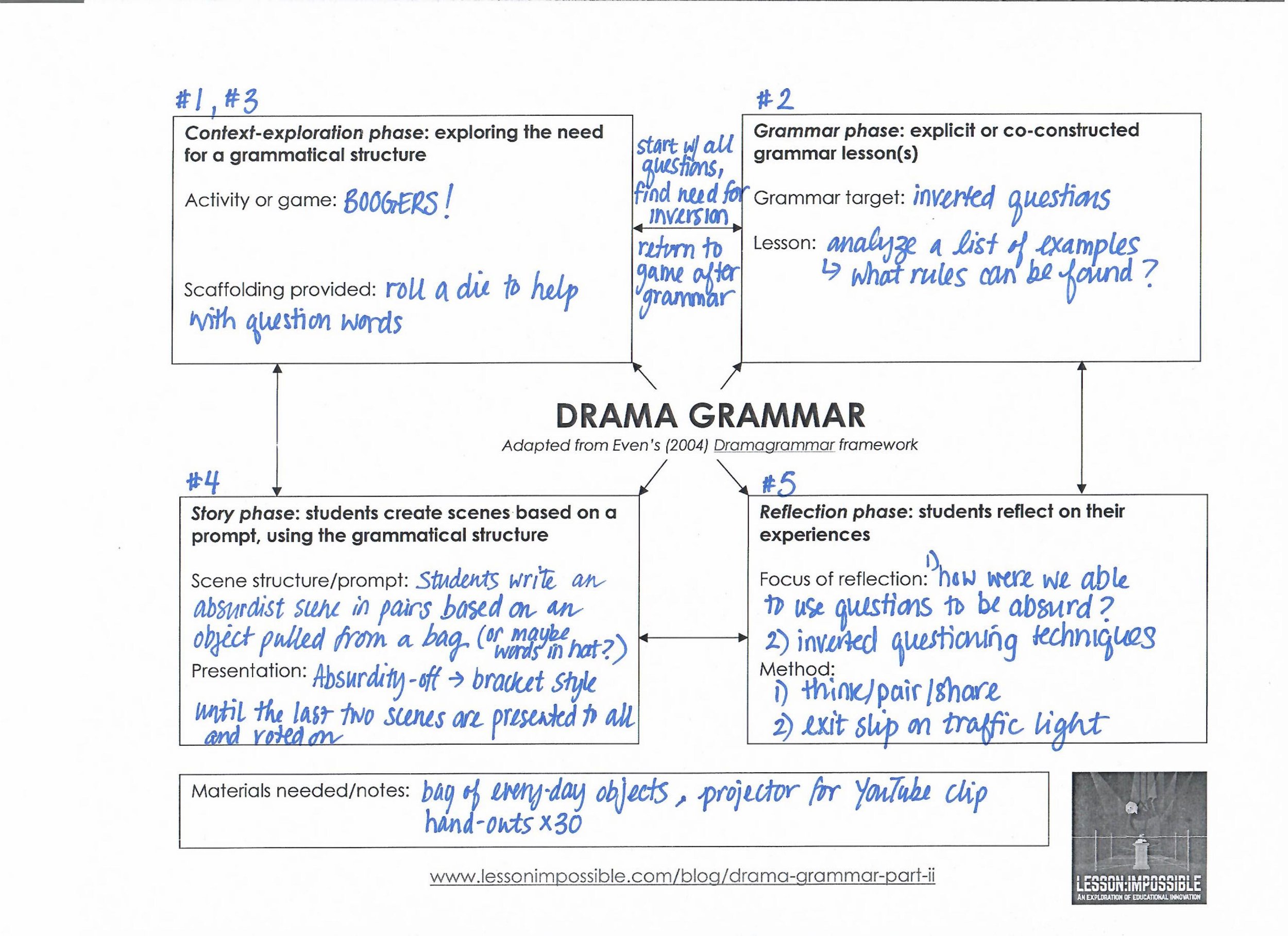

I’ve made an example of how I would use this model for my own lessons. For example, if I were to do adapt my Theatre of the Absurd lesson, which deals with inverted questions and absurdist story telling techniques, to a Drama Grammar framework, I would plan it out like this:

You can see that we start in the context-exploration phase, go into a grammar discussion, and then return to the same game (the delightful BOOGERS!) to re-explore with our new knowledge. I also am still unsure about the prompt I want to use for students: should it be a bag of objects or a hat full of words? Some classes might not need to prompt at all, and some might need more structure. I also have students presenting to each other and then only two groups presenting to the class. As for the reflections, I broke it into two: one think/pair/share about our understanding of the absurdist genre (reflecting on understanding and performing) and an exit slip (reflecting on grammar; I’d likely have students put two questions on a sticky note, then place it on a traffic light I have in the classroom to signal how well they think they understand inverted questions (red=still struggling; yellow=think I’m getting there; green=I feel very confident). One thing to think about is how the new knowledge is going to be reinforced after the lesson. Like Even had in her sample workshop, perhaps there will be a homework assignment? If I were to stick to my original lesson for the Theatre of the Absurd, students would write new scripts independently and I would check them over the next class.

What are your thoughts about how I’ve adapted the original Drama Grammar method? What adaptations would you want to make to have it fit in your own classroom? Share in the comments!