Your language teaching mission, should you choose to accept it, is to use charades as a method for introducing or reviewing grammar or vocabulary.

I have memories of being a kid and peeking through the staircase and watching my parents and their friends play charades in the living room. I also remember thinking “I could’ve acted that movie title out better than Uncle Fred did!” Then, when I became a language teacher, charades became a class favorite improv game for reviewing or introducing grammar or vocabulary.

What started at a parlor game in 16th century France has evolved into a fun, simple, but incredibly effective game to play in the language classroom. The basics of charades are:

At least two teams competing against each other

A person mimes (silently acts out) a prompt

Their teammates must shout out the correct answer

Within a set timed limit

And fun is had!

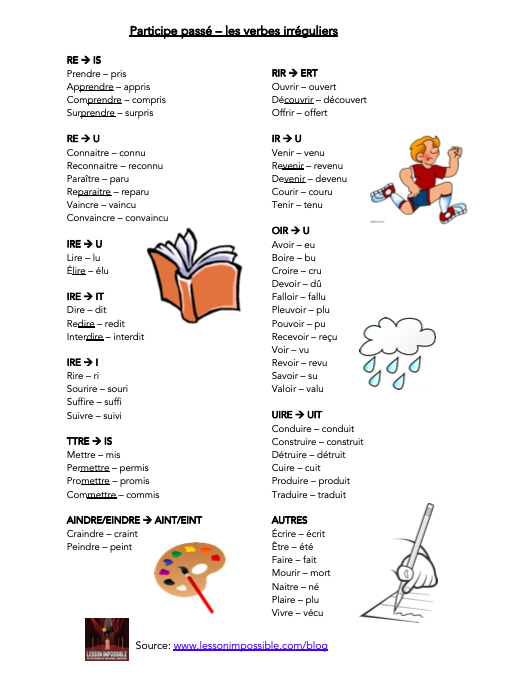

In my opinion, charades is best played with lists of vocabulary* or verbs. For example, in French students need to memorize the irregular past participles of verbs**, which can be quite boring. However, by doing past participle charades, students are incentivized to not only learn the correct past participle, but to make sure they know the meaning of its verb, since they’ll need to act it out or recognize it. (See below for adaptations of difficulty when using verbs).

Preparation before class:

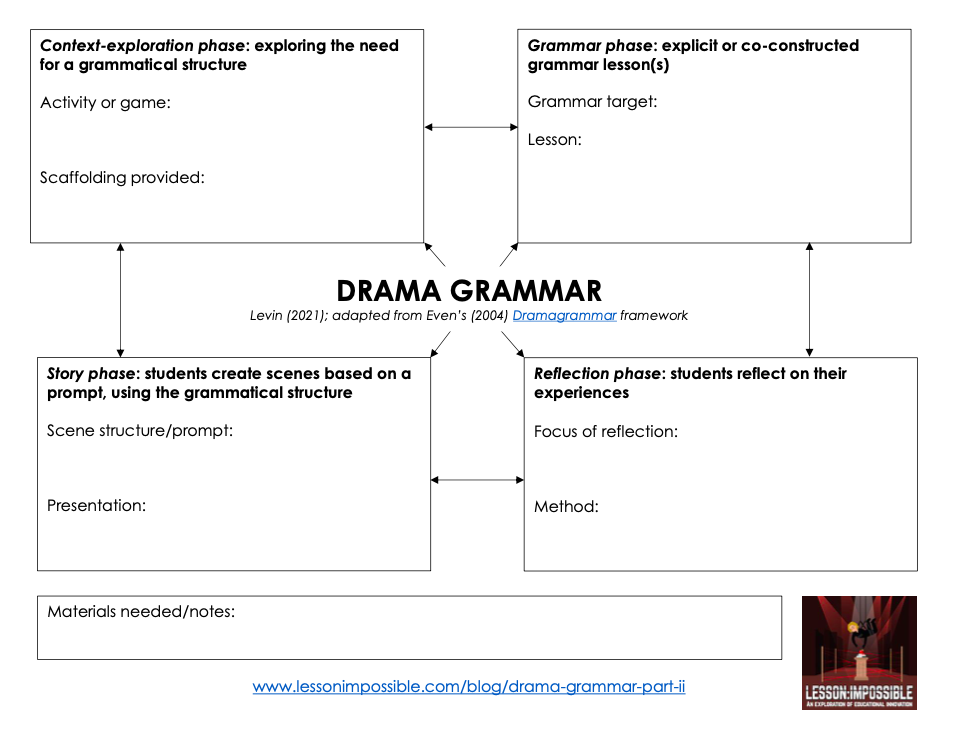

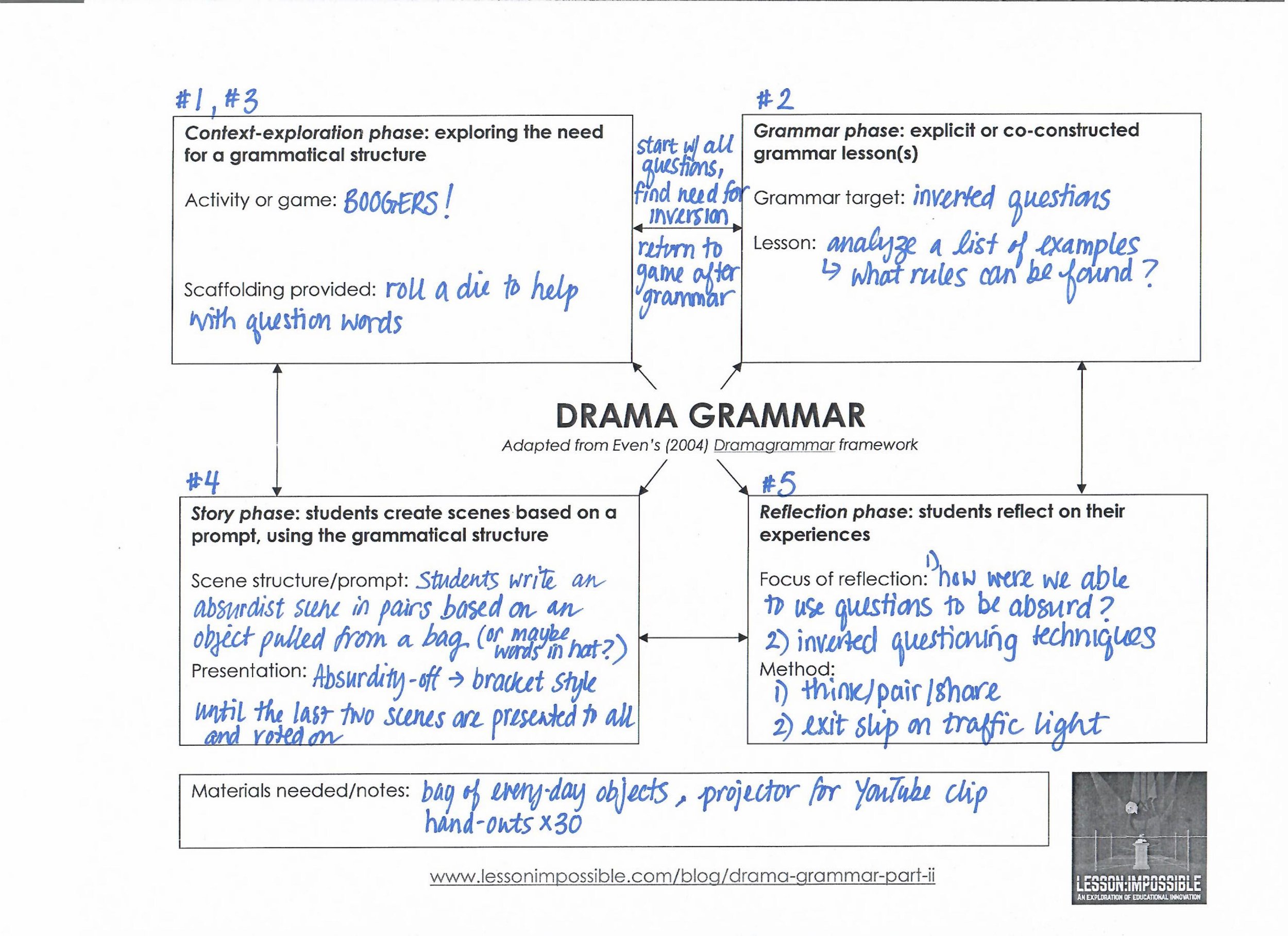

Find a place for this in your lesson plan. Maybe this is to review before an assessment? Or you are using the Drama Grammar method, and this is perfect for the ‘context exploration’ part of the lesson (in which case you’ll want to create some support materials to help students). Budget between 10-15 minutes, depending on how familiar students are with the game already.

Create a list of prompts (ex. specific verbs, irregular past participles, the unit vocab words in the target language, etc.) and print it out. Cut the prompts into individual small pieces of paper, then put in a container (i.e. envelope or Ziploc bag). Since I’ll often have five groups of six in a 30-person class, I tend to use five different colors of paper. That way if I find a random piece of paper when class is over, I know which bag to put it back into!

Before the activity:

Divide students into groups. As mentioned above, I like smaller groups of three competing with other groups of three. This way there’s two people guessing, which is small enough that students can’t just sit there. They also are guaranteed at least a couple of rounds of acting out the prompts.

Set the ground rules. Are participants allowed to put prompts back in the bag if it’s taking too long for their teammates to answer or they don’t know how to act it out? Are they allowed to have access to their notes when guessing and/or acting? If they violate the rules of charades (speak aloud or spell out a word) do they get any second chances or are they disqualified? If someone shouts out the correct answer right after the timer sounds, does it still count? I usually let each group decide for themselves.

During the activity:

The team with the most points wins the game. Points are gained when students on the person acting out the prompt’s team shout out the correct answer. There is a time limit (I usually do a minute, but that can be negotiated ahead of time) and the goal is to get through as many prompts as possible (gain as many points) during that time. The winner is declared when all prompts have been exhausted. As most students have access to phones with timers, I’ll have each group individually time themselves. This wikihow video explains how to play quite well.

While students are playing, I usually circulate to make sure everyone is on-task. If I see a student struggling, I might look at the paper and suggest a gesture or action for them to try. Because of the competitive nature of the game, there’s often a lot of engagement… and sometimes, too much noise!

After the activity:

I’ll sometimes follow up with a reinforcement activity, like a crossword** or a quickwrite, to solidify the learning in students’ minds. You can also have students do a quick reflection about how they did, and which words were the hardest to remember. Perhaps they could think of tricks of how to remember that word for next time? Students could also be asked to nominate an MVP of the group, whoever acted the best or guessed the most. Don’t forget to have students collect the prompts and put them all back into their container before you move on to another activity! There’s nothing worse that scrambling to deal with tiny scraps of paper between classes.

Adaptations:

Do a round-robin style tournament where teams compete for the title of ultimate charades champion.

Do a whole-class version where either half the class guesses, or it’s a free for all (depending on the class, this could get raucous!)

Transition to a game of Pictionary after warming up with charades, or vice-versa.

Add in obstacles. For example, “for the next three words, you can only use your hands to act” or “you must stand on one foot for the next two words”. You could brainstorm a list of possible obstacles with the class, and pull one out of a hat every round. Or, you could throw them into the bag with the prompts, so when students pull out a suggestion, every once in a while, there’s a random obstacle added!

If playing with verbs in a target language with conjugations, you can start easy (have students guess the infinite) and then make it progressively more difficult. I do this by having a die that students roll. In French there are six conjugations for each verb, which makes it very easy! So, for example, if a student rolled a three at the beginning of their turn, all the guesses for that minute must be properly conjugated in the third-person singular form. If the conjugations are wrong (and you bet the opposite team will be monitoring!) then they can’t get the point until it’s conjugated correctly. You can even have multiple dice for more advanced classes: add in a die for different tenses!

If you need a fun game to play to fill time or as a reward, play charades like my parents did in their living room: have students write down famous movies/films/shows and guess the title in the target language

*In my interview with Florencia Henshaw and Maris Hawkins they make the point that giving themed vocabulary lists is not evidence-based best practice. However, that doesn’t mean that you might not generate more meaningful vocabulary lists in other ways, such as through reading a class novel, music video presentations, or words that come up through a story if you do TPRS. You might also be in a situation where you are obligated to test students on certain vocabulary, and this is a way to make that rote memorization more engaging.

**French-specific resources (in PDF form):

List of French Irregular Past Participles (info sheet for students)

Irregular Past Participle Charades (to cut into prompts)

French Irregular Past Participle Crossword (to reinforce learning)

Have you played charades with your classes? What kind of prompts do you use? Any tips or adaptations to share? Post below in the comments!